Shearwater 2026: repaired, sanded, painted, oiled.

New sails made by our traditional sailmaker, Barry Quinn (Outer Harbour).

New wire shrouds, new stainless-steel turnbuckles and shackles.

Old boat (1984) sturdy as ever….

Author: Chris Wells

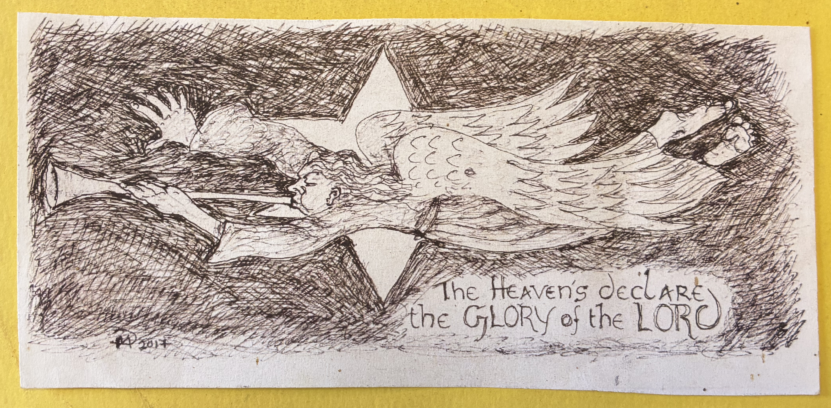

The road goes ever on 8

Ark 1

Elder 3

Elder 2

Yew

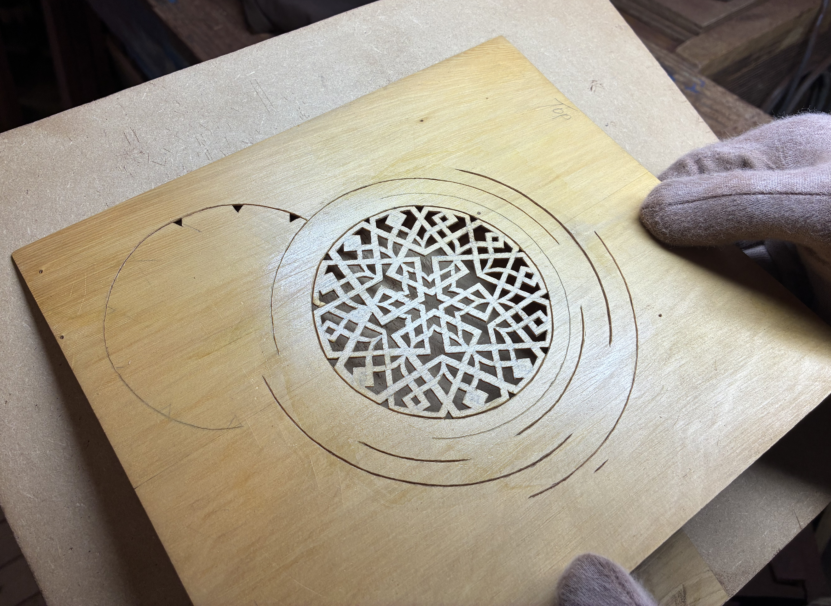

Circle 2

Bit by bit

This project fulfills Dad’s philosophy of ‘bit by bit’. I devote a maximum of fifteen minutes each day to the sawing of Pink Gum, the toughest wood around.

It also illustrates the associated observation: ‘less is more’.

I envisage three boat sculptures (assuming the wood is sound) – and on the way, get plenty of time to think about what might be….