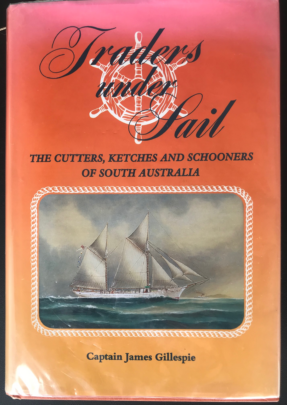

Back in December 2020, (my brother) Jonny and his family gave me a wonderful book: Traders under Sail: The Cutters, Ketches and Schooners of South Australia.

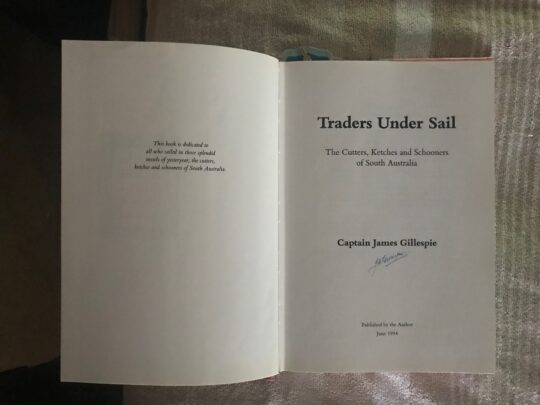

Traders under Sail is a solid, hardback publication – and for those of you who are bibliophiles, I should add that my copy is a first edition (June 1994) in excellent condition – signed and published by the author, Captain James Gillespie.

If ever you come across a copy, be it ‘excellent’, ‘very good’, ‘good’ or ‘acceptable’, I suggest you grab it – preferably by lawful means. My own copy is a gift which (as the saying goes) keeps on giving. I read a little every day, and once I reach the end I return to the beginning – just as Dad did with his cherished copy of The Wandering Years.

Here is a random sample:

The ketch ‘Morning Star’ of 15 tons was built at Port Adelaide. Her official number was 55606 and her dimensions were L 35.4′ x B 11.0′ x D 4.8′. In 1874 she was lengthened and her new dimensions were L 47.3′ x B 11.3′ x D 4.8′ and her tonnage was increased to 17 tons.

The ‘Morning Star’ was first owned by T.Heritage. In 1876 the ownership was transferred to J.Styles; in 1885 to S.J.Bishop; in 1886 to G.Albert and R.Quin, then to Albert and Christie; in 1894 to J.D.Edwards, and in 1898 to W.Loveder who had her for about 10 years, thence to T.Young, W.Christie and J.Wallace in partnership, and finally to H.Gibbons.

This little vessel traded for over 50 years and she was well known in the trade between Port Adelaide, Port Gawler and Port Wakefield. She was wrecked at Glenelg in November, 1923.

A straightforward account, maybe – but if you take time to read between the lines, you may discover elements of romance, and even the bare bones of a novel. I’m afraid many of our coastal ketches ended their days at the bottom of the ocean. I had assumed most of them would enjoy honourable retirement – but not so. More often than not they were wrecked mid-voyage (or ‘broken up at Birkenhead’), and the long South Australian coastline is littered with sunken remains of ketches and schooners and the like. These southern waters can be treacherous at any time of year, especially duirng the winter months. A safe anchorage may suddenly become a ‘lee shore – and as far as I know, there were no weather forecasts in the days of coastal trading – save the ones based on nautical intuition and experience….

Below is a portion of log entries by Captain William Thomas, master of the trading ketch: Duchess of Kent (1880).

Nov. 15: Picking up logs etc. 16th loading barley.

Nov. 20: Picking up kedge. Sailed at 5.00 am.

Nov. 21: ‘Emu’ passed down. ‘Flinders’ passed up. Arrived Moonta, 8.30 am.

Nov. 22: 7.30 am loading copper ore, 58 tons. 12 noon hauled off to anchor.

2.00 pm under weigh. ‘Daniella’ and ‘Maldon Lewis’ passed.

Nov. 23: Splicing topmast stay. Caught a dozen Tommy Roughs.

Nov. 24: 2.00 pm off Wardang Island. 11.00 pm off Corny Point.

Nov. 26: ‘Lady Daly’ astern. Anchored Snapper Point 1.00 am

Nov.27: Pulled to Copper Coy’s wharf, discharged ore.

December 1: Sailed to dock, discharged barley

Dec. 2: Married at St. John’s Church Salisbury.

Dec. 3: Loading timber and oats etc.

Dec . 8: Cleared up. Sailed to Snapper Point. 9th cleared river 8.00 am. Beating all day. South wind. 6.30 pm stood across Gulf from Noarlunga.

Dec. 10: Althorpe 7.00 pm. Corny Point midnight.

Dec. 11: Off Wardang 5.30 am. Arrived Wallaroo 4.00 pm.

Dec. 13: Handed alongside ‘Annie Lisle’, discharged and sailed for

Port Germein at 3.30 pm.

Dec. 14: Calm. Rafted timber ashore.

Dec. 15: Discharging at jetty.

Dec. 17: Hauled vessel on beach. Discharged general and commenced

loading wheat…..

Well, I assume Captain William Thomas had a reasonably dry sense of humour. He might, in addition, have been a pragmatist: humour and pragmatism often work in tandem. I see that he is back loading timber and grain on December 3rd – and then he takes a few days break….whether as planned, or because of unfavorable winds, we will never know.

On the 8th of December he begins the return voyage to Port Adelaide – and I like to think that his newly-wed wife joined him on board. It would have been an unusual event, but not without precedent, at least in the world of the tall ships.

One example immediately springs to mind.

In December 1870, Captain Joshua Slocum, master of the Washington, 332 tons, arrived in Sydney with a general cargo – and departed in company with his wife of two or three weeks, Virginia Walker. She spent the rest of her short life on board: devoted wife and mother, counsellor, advisor, business partner – even navigator. When she died at age 34, Slocum was devastated; indeed, we are told that he never fully recovered from the tragedy.

Of course he went on to achieve great things: an astonishing adventure in the canoe, Liberdade; a voyage alone around the world in the indomitable small sloop, Spray; the subsequent writing of (surely) the greatest maritime book of all times – and his final, mysterious quest from which he never returned.

As to the mystery – I cannot help thinking Slocum’s early loss may well have had some bearing on that last voyage beyond the sunset and the baths of all the western stars – in search of whoever or whatever he was seeking.

It may be so.

But I seem to have drifted a little from our familiar gulf waters, and the sturdy trading vessels going about their business.

Returning to random samples:

Aristides, built in 1902 at Battery Point, Hobart by R. Kennedy and Son.

Official number: 104694 .

Dimensions: L 80′ x B 21.9′ X D 7.1′

Registered at Port Adelaide in 1810 by the SA government.

Purchased in 1924 by J H Murch.

Offered for sale in 1929….

At the time of the sale, Captain Tom Spaulding inspected the vessel on a slipway, and being satisfied that she was sound, and would suit his purpose of trading between Tasmanian ports and Melbourne, said that he would purchase the ship if the vendor was prepared to take the auxiliary engine out. He wanted no part of these modern inventions and preferred to rely on the power of the wind and his own skill as a sailor. The vendor was happy to comply with the conditions of sale and had the engine removed.

In this brief paragraph, our matter-of-fact author lets down his guard for a moment. We can see that he and Captain Tom Spaulding are kindred spirits. They share a love of the traditional maritime skills; a particular philosophy of time, and timing; a belief in the power and grace of the natural world; an understanding of the otherwise hidden calligraphy of tides and currents; a (prescient) faith in the practicalities and potential of wood, wind and ocean.

Yes, on the basis of those few lines, I could write a book about Captain Tom Spaulding. And I feel sure that Dad,too, would have warmed to his practical philosopy; he had faith in the old ways and means – the old philosophies. He firmly believed that coastal trading, for example, would eventually return to our southern shores. Indeed, his four sons inherited the same conviction – or you might say, dream – whichever the case may be.

In my view, traders under sail will sooner or later be revived, of necessity. I am not talking about those contemporary vessels with rotating, metal ‘sails’ operated by computer. They scarcely fall into the category of sailing boats: in their case, beauty has been overlooked in a single-minded pursuit of efficiency. But it need not be so. The old coastal traders combined beauty and function – wood and canvas – in full measure. And of course, the wind is free: it keeps on giving.